Proven: Diet and Gut Bacteria Affect Cancer Risk

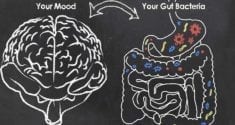

Every moment, there are trillions of microorganisms residing in your digestive system. Some of these species of bacteria are beneficial, while others are harmful. Though one of their main functions is to help you digest food, in the past few years scientific research has revealed that gut bacteria impacts many aspects of health, including your metabolism and immune system. For example, babies born by C-section are more likely to have immune problems like asthma and allergies. This is because babies born vaginally receive beneficial bacteria from the mother's vagina that strengthen their immune system.

As research continues to look into the link between gut bacteria and the impact on various aspects of health, among the growing list of health concerns that can be influenced by an unhealthy gut microbiome is colorectal cancer.

Gut Bacteria Affect Cancer Risk

According to the National Cancer Institute, colorectal cancer is the fourth most-common type of cancer. It is estimated that in 2017, there were approximately 95,500 new cases of colon cancer and 40,000 new cases of rectal cancer in the U.S. alone. Given how common this disease is, research surrounding prevention and treatment is of great importance to public health. A new study, published in the journal Nature Communications, reveals that there is a deeper connection between colorectal cancer risk and gut bacteria than previously known.

This study involved isolated mouse and human cells and focused on the role of short-chain fatty acids, or SCFAs. SCFAs are chemicals produced by the gut bacteria during the digestion of fruits and vegetables, and have many possible subtle health effects due to their ability to enter the human intestinal cells, affecting gene expression and cellular behavior.

The researchers found that the presence of many SCFAs in the human digestive system can increase crotonylations; protein modification that can switch genes on or off. These crotolynations are produced by inhibiting a protein called HDAC2. High levels of HDAC2 have been previously linked to an increased colorectal cancer risk. Mice with a low overall gut bacteria population were found to have higher HDAC2 levels, suggesting that a thriving internal microbial ecosystem is important for reducing cancer risk. In a nutshell, a diet high in fruits and vegetables will cause greater SCFA production, which in turn inhibits the HDAC2 protein which is linked to colorectal cancer.

Fiber and Your Microbiome

How can fruits and vegetables protect against colorectal cancer? One of the biggest factors is their fiber content. Another study, conducted at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts and published in the journal JAMA Oncology, found that a high-fiber diet, specifically, is protective against colorectal cancer. A high-fiber diet consists of plenty of fruits, vegetables, beans, legumes and nuts, as well as whole grains instead of refined grains.

How can fruits and vegetables protect against colorectal cancer? One of the biggest factors is their fiber content. Another study, conducted at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts and published in the journal JAMA Oncology, found that a high-fiber diet, specifically, is protective against colorectal cancer. A high-fiber diet consists of plenty of fruits, vegetables, beans, legumes and nuts, as well as whole grains instead of refined grains.

Though the gut microbiome is usually talked about in very general terms, since there are potentially millions of different bacteria species that inhabit the human body, individual species have been linked to specific aspects of health. One species of bacteria, F. nucleatum, is highly suspected to play a role in the development of colorectal cancer. In other research, it has been found that a high-fiber diet reduced numbers of this bacteria. This at least partially explains the mechanism through which a high-fiber diet reduces colorectal cancer risk.

This link between dietary fiber intake and colorectal cancer risk can be considered legitimate, as the study was very large. It used data from over 137,000 people who were part of the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and the famous Nurses' Health Study. By contrast, the researchers found that a diet high in red meats, such as beef and pork, and processed meats such as hot dogs, may increase the risk of colorectal cancer.

Gut Bacteria and Chemotherapy Effectiveness

Your gut bacteria not only influences your cancer risk, but how well you will respond to cancer treatment. A review of research, published in the journal Nature, has shown that the gut microbiome affects how a patient will respond to chemotherapy. Since your gut bacteria and immune system are in constant communication, your intestinal bacteria can alter your immune system's reaction to chemotherapy drugs. The microbiome can also affect the activation of the drugs themselves.

The relationship between gut bacteria and cancer treatment effectiveness has also been explored in multiple animal studies. Mice who have been raised in a sterile environment since birth, and who therefore have no gut bacteria whatsoever, have higher levels of the liver enzymes that break down chemotherapy drugs. This means that the drugs are broken down faster, therefore leaving the animal's body faster, giving the drug less time to act and making it less effective. Since many human chemotherapy drugs are delivered in an inactive form, to be later activated by liver enzymes, this effect of the microbiome is of great clinical importance.

Although further research on this topic is needed, in short, it appears that taking measures to maintain a strong and healthy balance of gut bacteria may reduce cancer risk as well as improve recovery rates in people who have already developed cancer.